How Indigenous-led, Community-based Conservation in Northeast India is Offering a New Paradigm in Conservation Practices.

Thanamir is a village in Nagaland, north-eastern India that manages a 65 square-kilometre forest teeming with wildlife. Through community collaboration & local tradition, they’ve bucked the global trend of biodiversity loss.

Above: Thanamir Village (top left) alongside the community forests & fields (Ramya Nair, 2021)

Conservation, during the last century or so has been dominated, on the whole, through the paradigm of national parks and sanctuaries. These practices have stemmed the bleeding of many endangered or threatened species, thus having helped conserve some of Earth’s most precious wildlife. This has allowed for the growth and stabilisation of many species that were deemed certain to be going extinct, for example, the Arabian Oryx and the Californian Condor. However, these strategies are – or should be, viewed as a sort of break-glass-in-case-of-emergency protocol and not standard procedure when wanting to preserve wildlife. An alternative to old-style conservation is community-based conservation, where efforts to protect wildlife biodiversity are actively managed and come from within the community. This practice has seen exceptional success with the indigenous-led conservation strategies carried out by the communities of Nagaland (Northeast India), which is home to an immense level of thriving biodiversity.

An issue with the current paradigm is that it tends to be more reactive than pre-emptive and often involves removing the wildlife from its natural habitat, as the ecosystem has become degraded and can no longer support the organisms within itself. This is done to stabilise populations with the intention of reintroduction at a later date, however, this leads to the ecosystem experiencing further degradation and could lead to other ‘forgotten’ organisms in the system suffering, causing irreversible damage. This practice is carried out as an emergency measure and, in most cases, increases threatened populations. Despite this, ecosystems, wildlife and habitats should be pre-emptively conserved and managed to prevent this destructive (albeit, necessary) practice from occurring, to begin with.

To the left: a clouded leopard, captured by a trail camera in the community-owned forest.

(Images: WPSI / Thanamir village)

The Northeast region of Nagaland, India holds immense potential for the long-term conservation of wildlife due to its stunning levels of biodiversity, locally owned forests and the instilled connection between its citizens and the natural environment. The community of Thanamir is living in harmony with the local wildlife through indigenous practices centred on community-ran forests. However, Thanamir doesn’t rely upon vast protected parks forbidding human activity. Quite the opposite – as 88% of Nagaland’s forests are community owned. The forests are still a part of community activity including walking, hunting and logging. Although this can seem like an oxymoron, these activities have been carried out in harmony with the natural equilibrium for generations as these traditional customs are not exhaustive.

Each village has its own forest with different management systems, with governance run through village councils. Student unions can play a significant role in the councils, ensuring new ideas and ways to optimise forest governance are consistently being brought forward. This unique form of administration allows for the upholding of traditional and local customs, the continual inclusion of local’s interests and the introduction of new ideas which improve life for the citizens and wildlife. For example, in 2014 Thanamir student union instituted a partial ban on hunting in about 5% of the forest and also seasonal hunting bans in other areas to safeguard certain species and ensure a thriving environment. These policies complement the species-specific bans on hunting across the whole of the forest which is used to protect endangered species. These include hoolock gibbons, sambar and tigers. With the forests of Nagaland having stable populations of native species, if nearby environmental areas are connected via ecological networks and corridors it would allow for the revival and stabilisation of threatened populations of wildlife across the Indian subcontinent.

Despite the wildlife of Thanamir forest flourishing, the local community actually reached out to the Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI) first to understand just how many species lived in their forests and how to conserve them long into the future. There had never been systematic research done in the area, so the team wanted to create robust socio-ecological baselines of not only the range of wildlife present but also the population sizes too. This would then allow the team to give tailored recommendations on forest management that link the community and ecological spheres. As the village and the forests are intertwined, the research focused on the intricate network and links between the community, wildlife and the environment. This creates a sustainable model for the future that is mutually beneficial for all parties. The WPSI’s research incorporated heavy community involvement at every stage through placing camera traps, terrestrial wildlife observation and birding while otherwise, the villagers carried out their livelihoods. Heavy community involvement in the research teaches the villages some modern conservation and observation techniques that they can continue independently alongside their livelihoods to help monitor and safeguard wildlife populations.

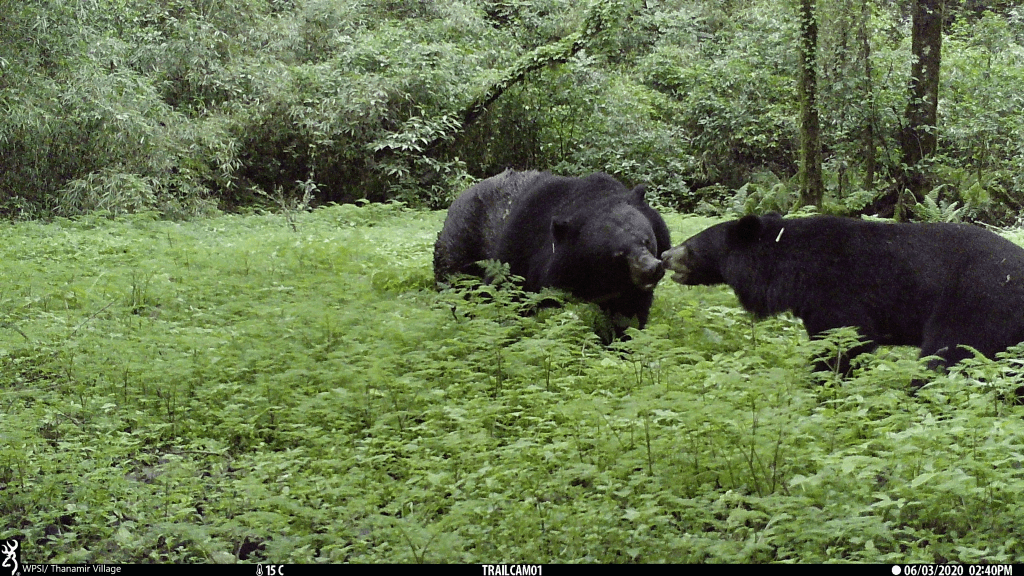

The research that the WPSI conducted uncovered an abundance of wildlife and a vast array of species. These included 23 mammalian species which included: clouded leopards (pictured above), Asian golden cats, marbled and leopard cats, Asiatic black bears (pictured below), Indian muntjac deer, red serrow (a species of wild goat), giant squirrels, spotted linsang, Assamese macaques and stump-tailed macaques – among many more. Furthermore, in only three months of observation, the team have documented over 210 species of bird with potentially many more to be catalogued. The site where hunting was restricted (not forbidden) was found to have a thriving bird population which reveals how partial bans can alleviate pressure on species thus allowing their people to thrive whilst respecting indigenous rights and customs to hunt in harmony with the forest. The sheer volume and range of wildlife species in a relatively small (geographically speaking) area shows how these forests are an incredibly diverse and complex assemblage of organisms that have been shielded from global biodiversity trends through indigenous and community management.

Above: Asiatic brown bears caught on a trail cam in a Thanamir forest.

(Images: WPSI / Thanamir village)

One way the WPSI aims to ensure the long-term stability of the wildlife in the forests and the community of Thanamir is through harnessing ecotourism. Despite some trekkers coming through the village on the way to Nagaland’s highest peak (Mt Saramati), there is no ecotourism being practised in the area. Due to the unreliable nature of income in the area, this could lead to (in times of crisis) pressure being put on the forests and value being extracted from them. As long as there is monetary insecurity in the area, there is always an extant threat to the sustainability of the forest and the native wildlife populations. To help minimise any possibility of this happening, the WPSI is training the villagers to become bird guides and to be able to take tourists on guided tours of the forests, relaying their indigenous practices and bird identification knowledge. As a result of the high biodiversity levels, tourists could often observe 30-40 species in only one hour, many of which would include rare native and seasonal migrant varieties which would make the area a must-visit for nearby avian enthusiasts.

The utilisation of ecotourism would provide the community with a sustainable, favourable cash flow that would remove any existing pressure that was on the forests to supplement their income. This would guarantee a healthy, thriving forest that still provides income for the community without extracting it from their local environment. Moreover, an indirect benefit of this new local industry would be that as many of the villagers now have stable incomes, they will no longer have to leave in search of work which would ensure the continuation of the area’s indigenous heritage, traditions and culture. Regardless of the many positive impacts ecotourism will have on the village, it is essential that its introduction and subsequent rollout are monitored and managed by the WPSI. If ecotourism is not carried out in the right way, it can be a detriment to the wildlife, for example in areas of dolphin watching the socialising and resting behaviours of the dolphins are substantially decreased due to tourist boat activity, which causes the dolphins harm and distress. Also, the environmental degradation posed by increased footfall and damaging touristic practices is another potential cause for concern. Although these potential negatives need consideration, they can be mitigated through constant monitoring and reviewing of environmental practices and their consequences on the ecosystem. Additionally, the potential of the long-term sustainability of both the community and the environment of Thanamir, provided by ecotourism, is too great to be left untapped.

” Local leadership is how these forests have been sustained for generations and that is how they will stay in Thanamir. The people have respected their local wildlife and forests for centuries without upsetting the natural equilibrium “

There are a few key reasons why the research in Thanamir and the community plan have been so productive and must be taken into consideration if any similar project hopes to replicate its successes. Firstly the community was the one that reached out initially to the WPSI which prevented the community from feeling imposed upon or being dictated to. Furthermore, the WPSI went into the project with nuance and sensitivity to Thanamir’s cultural heritage in regard to hunting, this understanding meant that they could avoid the issues and resentment that can build up in indigenous communities when all hunting is labelled as a destructive process and is holistically shunned. Indigenous hunting shouldn’t be eradicated in these landscapes as it vastly differs from the destructive practices that exist in other parts of the world. This level of hunting is sustainable and in keeping with the natural equilibrium of the environment, serves a cultural purpose and has been carried out for generations with the respect for wildlife and their ecosystems. Furthermore, the WPSI didn’t try to create a new framework for the village to live by. They only adapted Thanamir’s current framework to live as they do now while developing the monitoring of wildlife and ecotourism activities in the area. This ensures that any transition for the people is seamless and in keeping with their cultural heritage and traditions.

The people of Thanamir appear to have a sound, long-term and sustainable plan not only for the future of the astounding amount of wildlife in their forests but also a future for the culture and livelihood of their village too. Local leadership is how these forests have been sustained for generations and that is how they will stay in Thanamir. The people have respected their local wildlife and forests for centuries without upsetting their natural equilibrium. Now those forests are paying them back by preserving their local heritage and way of life by providing sustainable employment. The people of Thanamir deserve it.

” It is clear that both the scale of our conservation efforts and the methods we employ are simply not enough to prevent what is projected to be a biodiversity catastrophe “

The Earth is on the brink of crisis; between 1970 – 2018 global wildlife populations have been decimated due to land use change, environmental pollution and climate change, with an average of 69% of all species lost in that time span. It is clear that both the scale of our conservation efforts and the methods we employ are simply not enough to prevent what is projected to be a global biodiversity catastrophe. It is not a coincidence that the forests of Thanamir are abundant in wildlife. Local governance of the environment through the community is an effective conservation strategy and ensures the best interests of the people and wildlife are represented. You do not need vast protected areas or single-species animal sanctuaries to conserve wildlife if nature is respected and the balance is not tipped. Although these strategies have been crucial in preserving countless species that would’ve been extirpated otherwise, they are not a solution – only a reaction. If we truly want to conserve not only the species but the entire ecosystems of this planet, then the experiences and perspectives of indigenous people and local communities must be at the forefront of protected area management and design. The Earth is at a crossroads, lessons need to be learned from places such as Thanamir and implemented where applicable because if not, it will be too late before we realise we needed to change. Local indigenous governance could prove to be a powerful tool in the field of wildlife conservation and needs to be seriously considered worldwide because there’s still an incredible amount of digging to do and our other tools are blunt.

Leave a comment