A question that is seldom asked in public discourse is what are we rewilding to?

The question may seem straightforward on the surface – we’re just re-wilding. We’re improving the derogated landscapes impacted by human activity. However, as humanity probes deeper into the Anthropocene this only produces more questions that need answering – how do we know what to aim for and how do we assess the efficacy of our projects?

Firstly, we have to decide what is the wild we are trying to reclaim. There isn’t a fixed answer to this question, the ‘wild’ we are trying to reclaim can vary based on many factors and no place will try to achieve the same ‘wild’.

The first consideration is where is the area of the rewilding effort. As ecosystems function depending upon the biome they’re in, the first guideline for rewilding is location. You can only rewild depending on the ecological factors of the area – temperature, precipitation, soil composition etc. These factors directly impact the growth of biomass which in turn sets the stage for the local environment. The structure of the vegetation present in an environment can then in turn impact the climate of the area thus increasing the ecological complexity of the environment. There’s a reason the tropics are so rich in wildlife, it isn’t just because of the high productivity of these areas but also the structural complexity of their biomass which allows many species of animals to thrive through the vast amount of niches present within the environment. We can’t rewild every location the same, so the same blueprint wouldn’t apply. Each ecological factor must be assessed and planned for accordingly. There’s no point planting succulents in the tundra.

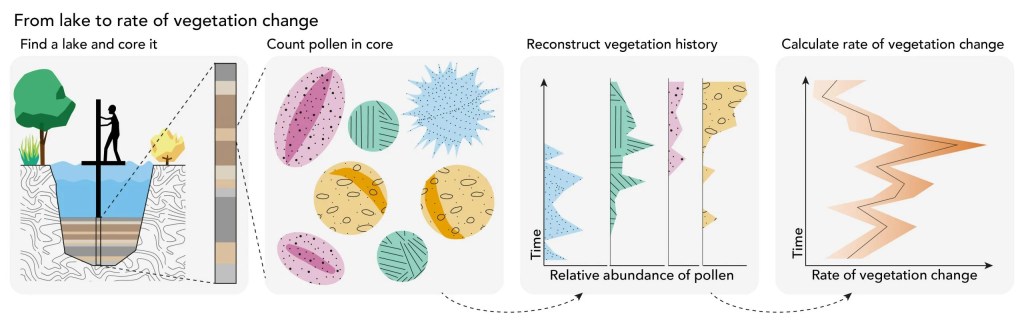

A further consideration is era of the wild is the target for the rewilding project. This is known as a baseline. Which baseline is chosen for the project influences the restoration effort that is needed. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in 2018 stated that “A target for restoration is a political choice, weighing social, economic and ecological factors, and it can vary by case and be revised over time.”. Once again this demonstrates how rewilding projects will be vastly different – and highly specialised- between different areas. Baselines for rewilding can be set from historical dates, as an objective to get back to the environment of that time. For example, you could aim towards an environment resembling the early Holocene (10,000 BCE -6,000 BCE) or pre-industrial revolution (-1,750 CE) either one will surely improve the area’s productivity and biodiversity, however, by choosing one you’re fundamentally changing the objectives of the project. We can reconstruct environments from the past via ice & peat cores, dendrochronology, pollen samples and stalagmite records. As we gather more of these environmental reconstruction techniques for an area, we can be more confident of a historical baseline and have a greater understanding of how to achieve this.

Figure 1: An example of how to reconstruct past environments through lake core pollen records (UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON. 2021.https://scitechdaily.com/fossil-pollen-shows-earths-vegetation-is-changing-faster-today-than-it-has-over-the-last-18000-years/)

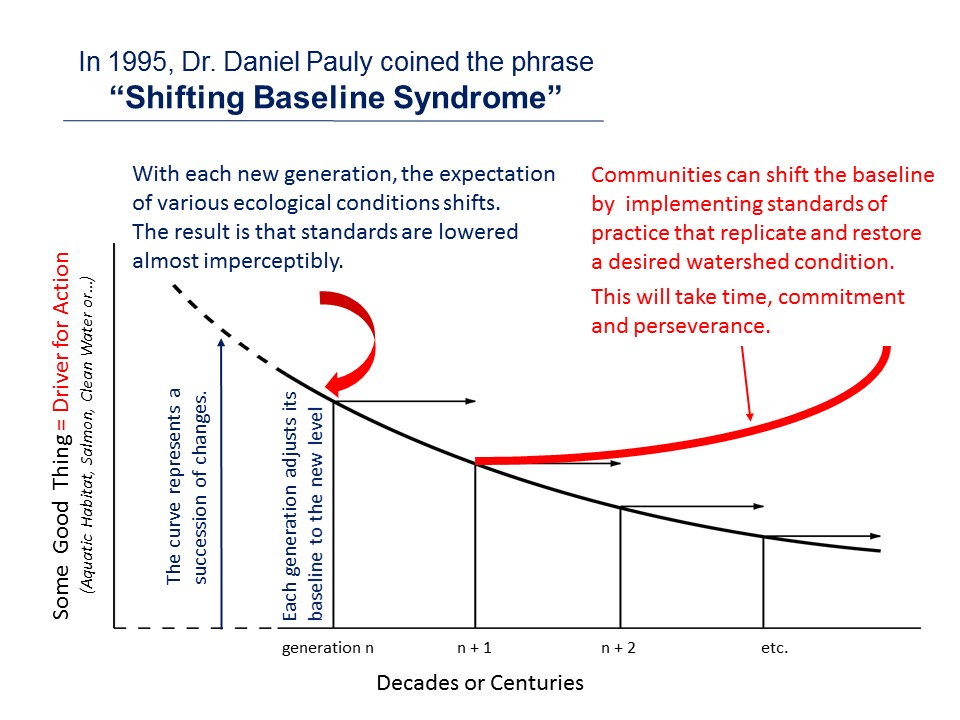

Unfortunately, we cannot shoot for the stars on every rewilding project. Not every environment can be restored to a pristine pre-modern natural baseline before human influence. Factors like ecosystem degradation and climate change pressures can heavily impact which baseline we’re feasibly able to achieve. While we mustn’t succumb to shifting baseline syndrome, we can objectively set realistic natural baselines that will not only improve plant and wildlife biodiversity but also improve ecosystem services. Once we start to improve ecosystem productivity and complexity, we can build for higher baselines and expectations of our environments. For example, we can accept due to climate change pressures that it’s not currently viable to return to a premodern baseline but we can return to a baseline that is more ecologically productive and robust to deal with future climate change impacts. We can introduce vegetation to an area it used to occupy and try to entice the wildlife back to an area naturally or we can go for a more top-down approach and reintroduce extirpated species like lynx, wild boar and wolves. Both of these methods will improve the natural functioning of the ecosystem and return it to a ‘wilder’, more historical state.

Figure 1: Graph showing the impact of Shifting Baseline Syndrome and how we can reverse it (The Partnership for Water Sustainability in BC. 2016. https://waterbucket.ca/rm/2016/01/12/the-shifting-baseline-syndrome-is/ )

Targets for rewilding do also not have to be based on a specific boundary but more specific, quantifiable objectives. For example, a population growth target of a keystone species to grow by X number or for a certain species of vegetation to grow by X hectares. These objectives can be easier to track and be a key tool to assess how close to a certain ecological boundary we are to achieving, however, this can be a more reductive objective and could ignore the functioning of key ecological processes in the local ecosystem.

To come back to our question “What are we rewilding to?”, there is no correct answer. The answer depends upon a myriad of factors that change from place to place. No two areas will be rewilded the same. Based on ecological quotas or through environmental reconstruction methods we can assess how ‘wild’ our current landscapes are and how much further we may have to go, however, how ‘wild’ an environment will be depends on the objectives and efficacy of the project. This is only scraping the absolute surface of rewilding and restoration objectives and the projects in the field have an innumerable amount of factors and considerations when rewilding an environment. However, as a whole, we are simply trying to improve the condition of our environment and provide our vegetation and wildlife with the highest chance of flourishing going forward. In sum, any historical or ecological boundary is desirable over the ones we are hurtling towards.

Leave a comment