Rewilding is a method of ecological restoration that has only started to permeate mainstream public consciousness in the last decade or so, despite having roots in academia that stretches further back. Although wilderness preservation and the idea of protecting ‘the wild’ is not a new idea, the concept of reducing human intervention, reintroducing species and allowing nature to self-regulate has only recently started to gain traction.

Before rewilding took root, the principal method of environmental policy was a largely human-centred management approach, with us being the custodians of the natural environment. This involved blanket protection zones of natural areas, for example, national parks, and species-specific conservation programs, most notably the famous captive Panda breeding program. These methods have had various levels of success, however, they fail to address the root of environmental issues and the degradation of ecosystem services. Protective areas are a good start to conserving what nature may be remaining but if there is no longer a productive ecosystem, you end up protecting an ecological desert. Whereas captive breeding programs can be vital at preventing species extinction, they take wildlife out of their natural environment, potentially condemning the ecosystem which cannot function without them, while removing any wild behaviours from species growing up in captive programs.

In comparison, rewilding aims to give nature back the tools it needs to self-regulate wildlife population, biodiversity and ecosystem services. Through reintroducing extirpated species and vegetation to a degraded landscape, conservationists hope to reinstate natural processes like seed dispersal, nutrient or water retention and predator-prey relationships. Although it requires human intervention to kickstart the process, once the seeds have been sewn, the idea is to allow nature to take its course and allow the knock-on effects of rewilding to revitalise the environment and wildlife with minimal human intervention.

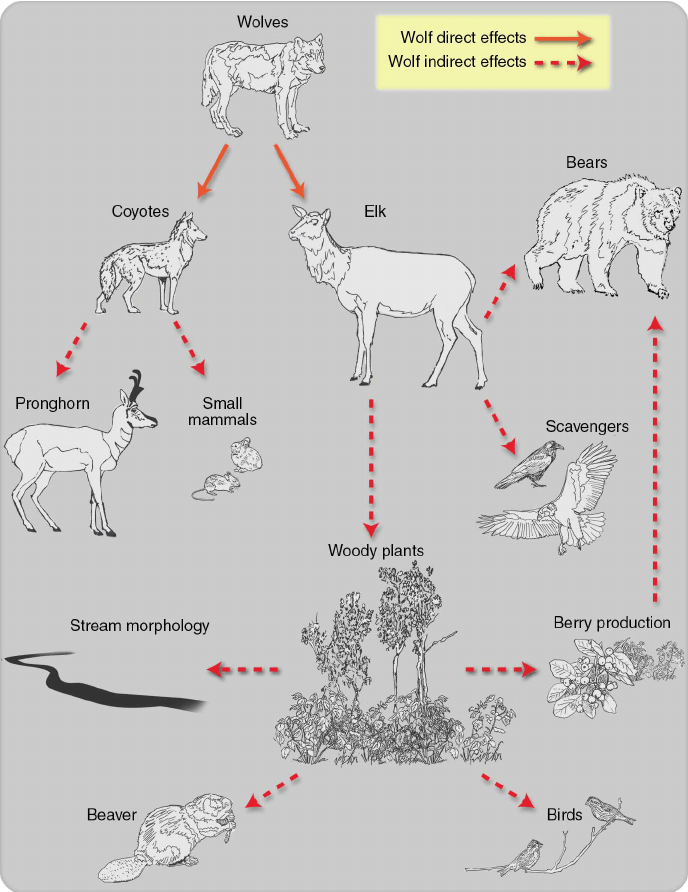

A cornerstone of rewilding is the reintroduction of keystone species. A keystone species is an organism that has a disproportionate impact on its environment and the rest of the food web through habitat creation and environmental regulation, which can cause trophic cascades. A trophic cascade is a process in which the action of one species can indirectly radically affect the local ecosystem—from soil and atmospheric composition to flood control. This process not only affects the environment but also reverberates through the foodweb. Trophic cascades are not always from the top to bottom and depend on what the keystone species is in question.

The most well-known example of a trophic cascade is the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone National Park. The restoration of the apex predator at first predictably altered the park, through the reduction in its natural prey – elk. The process of killing elk also encouraged populations of scavengers like eagles coyotes and bears. Not only did the wolves reduce the amount of elk, but they also altered their behaviour. Elk started to shelter in the dense foliage, rather than grazing in open pastures and on the riverbanks. This allowed vegetation to recover and provide habitat niches for many other species. With Elk now on the move, this allowed willow stands to recover, providing a food source for beaver colonies to thrive. This increase in vegetation stabilised the river banks and caused the river to change course. The increase in beavers (another keystone species) helped set off their own trophic cascade with their extraordinary ability to damn watercourses, create lentic environments and complex floodplains.

Ripple et al. (2014) showing the wolf’s trophic cascade.

Not everyone sees rewilding as the ‘silver bullet’ to the Earth’s environmental issues. Firstly, there are social issues that the native human population may not wish to deal with reintroduced species and conflict can arise with wolves, bears and beavers. Secondly, rewilding can be very resource intensive and it can take long timescales (decades) to see any progress or whether the project has even been successful. More importantly, however, shifting baselines caused by climate change may render rewilding redundant as species may not be able to survive in the biomes they existed historically. In this scenario, rewilding could divert important funding and attention away from technological innovations and climate change mitigation strategies.

“rewilding has the potential to revitalise our depleted environment and give biodiversity levels the shot in the arm they desperately need”

The Yellowstone wolves demonstrate the power of allowing nature to run its cause once given the tools it needs. It demonstrates why there is optimism behind replenishing degraded ecosystems worldwide. Rewilding adds structural complexity back into degraded environments, making them more resilient against external and internal pressures that they’ll undoubtedly face in the future. Although there are questions still to be answered with rewilding, in the grand scheme of things, it is obvious that rewilding has the potential to revitalise our depleted environment and give biodiversity levels the shot in the arm they desperately need. Our past attempts at conserving nature have not been effective enough. In the face of looming climate change and the current biodiversity crisis, it is no surprise how rewilding has become one of the jewels in the crown of conservation. If rewilding is embraced across the world, we may see Mother Nature given the tools it needs to self-regulate it’s systems on a grand scale. Although rewilding is not applicable everywhere and should not be the only tool utilised in conservation going forward, it is hard not to be optimistic about how it can lead to a much more ‘wild’ 21st century.

Feature photo by Neal Herbert/NPS

Leave a comment